Are Night Owls or Morning People Healthier? Neuroscience Reveals a Surprising Winner

Your body has a schedule, but are you listening?

You do not simply wake when you want to. You wake when your suprachiasmatic nucleus (a cluster of about 20,000 neurons in the hypothalamus) decides your internal clock has finished its nightly cycle (or just when your alarm goes off). You feel alert or sluggish depending on where you fall in a chronotype, a biologically influenced timing profile that shapes energy, mood, cognition, and metabolism.

We talk about morning people and night people as if they are personality traits, but neuroscience urges us to consider them as deep physiological patterns. The surprise is that neither chronotype is objectively “better.” The advantage depends on what modern life demands of you as well as how well your internal rhythms align with those demands.

Here is a more grounded look at what your body is actually doing.

I: What Chronotypes Really Are

Your circadian rhythm runs at about twenty-four hours depending on genetic architecture. The PER3, CLOCK, and BMAL1 genes help determine whether you drift earlier or later. About 40 percent of people lean morning, 30 percent lean evening, and the rest fall somewhere in the middle.

The timing affects more than just sleep. Research from the University of Birmingham and University of Surrey shows that chronotype predicts peak cognitive performance windows with real precision. Morning types perform best earlier in the day, with sharper working memory and mental stability. Evening types peak later, showing enhanced creativity and divergent thinking in the late afternoon and night.

Therefore, what you must consider is whether your schedule matches your internal timing.

II: The Neuroscience of Night Owls

Night owls tend to have delayed melatonin release, slower buildup of homeostatic sleep pressure, and greater resilience to sleep restriction in the late hours. They maintain higher activity in the reward circuitry during the evening, which has both benefits and risks.

Advantages

- Peak creativity in non-standard hours. Several studies (including a 2020 paper in Personality and Individual Differences) show that evening types outperform morning types on divergent thinking tasks when tested in the late hours.

- Flexible attention patterns. EEG recordings show that evening types maintain frontal-parietal connectivity later at night, supporting sustained attention into irregular hours.

- Greater innovation under low structure. Environments that reward autonomy often see night-leaning individuals excel.

Drawbacks

- Social jet lag. If society demands morning schedules, night owls experience chronic circadian misalignment, correlating with higher cortisol levels, impaired glucose regulation, and increased depressive symptoms.

- Cognitive penalties early in the day. Working memory and decision-making dip sharply in morning hours for night types. (I can relate.)

So night owl advantages only fully show up when life allows a shifted schedule. Without that, the biological rhythm becomes a liability.

III: The Neuroscience of Morning Types

Morning people have earlier circadian anchors, in melatonin rising earlier, core body temperature peaking earlier, and cortisol following a strong morning surge that supports task initiation.

Advantages backed by research

- Better synchronization with societal structure. Most schools and jobs begin early. Morning types rarely experience circadian misalignment.

- Improved long-term health outcomes. Studies in Sleep Medicine Reviews link early chronotypes with lower obesity rates, more stable glucose metabolism, and reduced cardiovascular risk.

- More consistent mood regulation. Morning types show stronger connectivity in the frontal control networks early in the day, which buffers emotional volatility.

Costs to consider

- Lower creativity in late-day conditions. Evening testing often reveals reduced flexibility and weaker associative thinking.

- Greater fatigue in late hours. Cognitive performance drops sharply past evening for early chronotypes.

- Rigid energy curves. Morning types sometimes struggle with unpredictable schedule demands, late shifts, or creative tasks that require extended ideation windows.

Morningness thrives in structured worlds. It can falter in environments requiring spontaneity or irregularity in patterns.

IV: So Who Is “Better” Off?

Here is the actual scientific answer:

You do better when the world matches your chronotype.

The most consistent finding across chronobiology is the cost of forcing an internal rhythm to fit an external schedule. Researchers call this circadian misalignment, and it functions like internal jet lag every day. It impairs memory formation, increases inflammation, disrupts metabolic hormones, affects cardiovascular function, and even shifts risk-taking tendencies.

Night owls suffer more because modern society is built around morning expectations, but they thrive in environments where people can choose their hours.

A 2021 University of Melbourne study found that when allowed to select their own sleep–wake windows, evening types perform as well as or better than morning types on executive function tasks.

The question is not “Which type is better?”

The question is “Does your environment punish your biology or support it?”

V: The Nuanced Middle

Most people are intermediate types. The research calls this “neither type” or “mixed chronotype.” They tend to have flexible rhythms and benefit most from stable routines rather than extreme schedules.

The nuance is this:

The best schedule is the one that creates alignment between circadian biology and daily demand.

For some, that is a dawn-focused rhythm. For others, it is a late-evening flow state. For many, it is a middle ground with slight adjustments.

Conclusion: Consider yourself in rhythms

The rhythm in your brain is older than culture, older than electricity, older than cities. It evolved under open skies long before clocks existed. So follow your rhythm.

This does not mean abandoning discipline. It means using discipline to protect the hours that work for you. If your peak focus arrives at 10 p.m., build your creative world around that window. If your clarity comes with first light, guard that time like a resource. Chronotype does not decide what you can achieve. It only decides when your work can feel less like a fight.

Productivity culture loves to shame the tired and praise the early. Neuroscience suggests something gentler: you are not lazy, disorganized, or poorly optimized. You are rhythmic. And when you move with your rhythm instead of against it, getting started on your to-do list becomes less about squeezing output from a fatigued mind and more about allowing your best self to arrive on schedule.

If You Could Skip Sleep: What the Latest Brain Science Says You’re Really Losing

A neuroscience and philosophy guide to the hidden work your brain performs at night and what happens to identity when those hours disappear.

Imagine waking up tomorrow and discovering that you no longer need sleep. Without drowsiness, dream cycles, hours lost to the dark… At first this feels like freedom, like more time to learn. More time to create. Like more life packed into the same number of days.

But current neuroscience suggests a stranger truth. The most important parts of your identity happen while you are unconscious. Rewrite the night, and you rewrite yourself.

Your Brain Uses Sleep to Rewrite You

Modern sleep science shows that the brain works through the night to revise your experiences.

• Targeted Memory Reactivation (TMR) research from 2024 demonstrates that memories cued during slow wave sleep become more stable and less emotionally reactive. Scientists played sounds tied to negative autobiographical events while participants slept and found that the next day, those memories carried lower stress signatures.

• A 2025 REM sleep study found that reactivating negative memories with an odor increased neural processing of the memory the next morning. The increase was not emotional intensification. Instead, it reflected deeper integration of the event with existing memory networks.

• New findings on adult born hippocampal neurons show that only a small population of cells replays waking experiences during REM. When researchers disrupted the timing of these neurons in mice, memory recall collapsed. The lesson is simple. Quality of memory depends on precise replay, not raw wakeful time.

If you lost sleep, you would gain hours, but lose the nightly work your brain performs to organize your life into meaning.

Extra Time Without Sleep Is Not Extra Life

People often imagine sleeplessness as a path to greater productivity. Yet sleep loss does more than create fatigue; it also changes the way the brain forms judgements and regulates emotion.

Consider two areas:

• Emotional regulation: Research from trauma therapy combined with TMR shows that sleep strengthens the results of therapeutic sessions. Patients who had sound cues replayed during sleep after EMDR showed reduced symptoms and increased slow oscillations that support emotional healing. Without sleep, emotional updates become inconsistent.

• Identity formation: Philosophers describe the self as a narrative process. Neuroscience now supports this. Sleep is when the brain binds semantic, emotional, and autobiographical memory into a coherent structure. If you removed that editing phase, you would not simply feel tired. You would feel scattered.

If you suddenly gained seven more waking hours, you would lose the nightly sense-making that keeps your personality coherent.

What Would You Do With That Time

If you did not need sleep, you would probably begin by doing what you already enjoy. Studying. Creating. Thinking. Reading. But without the biological systems that maintain attention, regulate mood, and integrate memory, the quality of those extra hours would change.

Work would become impulsive, as learning would become shallow, and emotional life would lose its gradients. You could accumulate more experiences, but you would have fewer tools to understand them.

Neuroscience suggests that sleepless productivity is an illusion, because, like it or not, sleep is what gives your wakeful hours their clarity.

Conclusion

If I had the ability to live without sleep, I would fill the extra time with projects that matter. Yet the newest research makes something clear. The cost of sleepless life is the erosion of memory precision, emotional stability, and personal identity.

Without sleep, you could do more, but you would undoubtedly understand less.

You would live longer in hours, but shorter in meaning.

The Plastic Instinct

How instinct and intuition shape us, and how the nervous system allows us to rewrite our oldest impulses

We usually imagine instinct as something permanent, a force that precedes thought and resists revision, moves faster than reason, feels older than memory, and often arrives before we have a chance to interpret it.

A sudden flinch, a tightening in the chest, a hesitation in front of a crowd; these are signals from biology’s first draft of the self.

Intuition, by contrast, feels learned yet inexplicable. It is judgment from experience, from patterns we have absorbed but cannot fully articulate. The distinction seems clear: instinct is inherited, intuition is acquired. Yet according to neuroscience, they are closer than meets the eye.

I. Instinct as the First Draft

Neuroscience shows that instinctive circuits through the amygdala, periaqueductal gray, and other subcortical structures operate at speeds that bypass conscious thought (LeDoux, 1996) in order to guide us toward survival. Instinct carries ancient wisdom, but it is not absolute, and in modern life some consider it an outdated architecture.

Instinct can change. Neuroplasticity allows the nervous system to reshape itself in response to experience, so emotional memory can be updated each time it is recalled in a process called reconsolidation (Phelps et al., 2009). Fear responses once thought permanent can be weakened through repeated exposure. Prosocial impulses can be reinforced through practice.

II. Intuition as the Brain’s Ongoing Revision

Intuition is the mechanism through which these revisions emerge through pattern recognition: the brain compressing thousands of experiences into a single instant of guidance.

A seasoned firefighter senses a building is unsafe before assessing the evidence. A guitarist feels the right chord before theory explains it. These are instincts refined by experience and practice.

The distinction between instinct and intuition fades because both rely on the nervous system’s ability to encode and adapt information. What feels immediate is often the negotiation between our ancient foundations and modern experience.

III. Rewriting Instinct and the Responsibility of Freedom

The possibility of rewriting instinct raises ethical and philosophical questions. If our deepest reactions can be altered, we bear responsibility for which impulses we cultivate. If courage can be trained, empathy practiced, fear tempered, then nothing stops us from imagining “ideal” humans—creatures optimized for rationality, cooperation, or moral virtue. History brings up a cautionary lens. Communism and socialism were once heralded as systems that could perfect society, yet the unpredictability of human behavior and the complexity of the world made total control impossible. Even carefully designed utilitarian experiments struggle to account for the emergent consequences of individual choices and the infinite ways context shapes action.

Maladaptive environments, however, can carve unhealthy patterns into the nervous system just as easily. The plasticity of instinct is both liberating and fragile. It allows us to grow, but it is also inevitably shaped by forces outside conscious control. In this sense, instinct is less a fixed verdict than ongoing revision. Human potential will perhaps always remain uncertain. We cannot manufacture perfection, yet we can still strive. So, the work of shaping instinct cannot be absolute; rather it fluctuates between what can be trained and what must be lived.

IV. Living Between Draft and Revision

Instinct is the prewritten framework of the self, a set of impulses we inherit before we can interpret them. Intuition layers experience atop it, shaping quiet guidance we rarely notice. Conscious attention is the instrument of our change, refining and redirecting without ever fully controlling the story.

Reflex can become deliberate as reaction can become understanding. We are neither prisoners of our earliest wiring nor masters of its total rewriting.

Rewriting instinct carries ethical weight. If courage, empathy, or fear can be trained, shaping the impulses of others through education, culture, or biotechnology is imaginable. History reminds us that attempts to “perfect” humans or societies fail, as the world resists total control. Yet this imperfection also carries hope: the same plasticity that allows harm also allows care, reflection, and responsible guidance.

To trust instinct is to honor its voice while recognizing limits. To engage thoughtfully is to co-author the self. Living fully must mean navigating the tension between inherited and cultivated impulses, letting both guide us. But this responsibility extends beyond personal growth. How we train instinct shapes the ethical contours of who we become. Courage cultivated in adolescence can influence moral choices in adulthood. Empathy reinforced through social experience alters how we respond to strangers. Fear tempered through exposure can prevent harmful overreactions. Shaping instinct means editing our identity. The ethical dimension is unavoidable: the self is inseparable from the impulses we refine, and the values we choose to embed in them.

References

- LeDoux, Joseph. The Emotional Brain. 1996

- Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 2011

- Damasio, Antonio. Descartes’ Error. 1994

- Phelps, Elizabeth et al. Nature, 2009

- Sapolsky, Robert. Why Zebras Do Not Get Ulcers. 1994

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

Should We Erase Painful Memories? The Neuroscience Behind Memory Editing

Memory-editing research is advancing fast. But removing our pain may also remove the person we became because of it.

There’s a question that keeps surfacing in neuroscience labs and ethical journals alike:

If we had the power to soften or erase painful memories, should we?

Researchers already know how to disrupt memory reconsolidation, which is the process by which a recalled memory becomes flexible before being stored again. Beta-blockers like propranolol have been shown to dampen the emotional intensity of traumatic recall in PTSD patients. Optogenetics experiments in mice have altered fear memories by re-tagging them with different emotional associations. Even human trials are exploring noninvasive stimulation to interrupt unwanted memories during sleep.

We are, quietly, entering an age where pain is editable.

But the more I read about these findings, the more a different question forms underneath the scientific one. Not Can we edit memory? But What happens to the self if we do?

The Problem with a Pain-Free Self

Memory is a fragile process, forever rewriting itself. Every time we remember something, we alter it slightly. Neuroscientists call this reconsolidation, but even without jargon, most of us know the feeling: a memory that once hurt becomes softer; another becomes sharper for reasons we can’t explain.

This plasticity is what makes memory-editing plausible, but it’s also what makes identity complicated. A life without painful memory might be easier, but would it still be yours?

Where Identity Lives

One of the more haunting ideas in cognitive science is that memory is less about accuracy and more about coherence. Rather than storing experiences like files; we reconstruct them to match who we believe we are now. The philosopher Daniel Dennett once suggested that the self is the “center of narrative gravity”, like a stabilizing illusion that helps us make sense of flux.

If that’s true, altering memory, scarily enough, changes the storyteller as much as the story itself.

A person who erases the memory of a betrayal becomes someone who never had to learn trust again.

A person who erases the memory of failure becomes someone without the quiet resolve that follows.

A person who erases grief becomes someone untouched by the shape love leaves behind.

One thing I continue to wonder is whether the edited self still be continuous with the original, or if the break in memory creates a break in identity too.

The Ethics of “Improvement”

There’s a moral seduction in self-editing. We are obsessed with optimization. Think better bodies, better habits, better productivity, everything in modern life. Why not better memories?

We know how important pain is, though. The fear of loss teaches us to hold people closer, and failure teaches us resilience. Even the most painful moments, those we’d give anything to erase, become part of how we find meaning again.

Neuroscientist Karim Nader, one of the pioneers of reconsolidation research, once said that memory’s primary function, surprisingly, is not to preserve facts, but to help us adapt. By that logic, even painful memories are functional. They help us navigate danger by recognizing patterns.

So when we “improve” ourselves by removing them, we risk becoming someone optimized, perhaps, but hollowed, a self that is easier to carry but harder to recognize.

The Risk of Losing the Lessons Without the Pain

The most compelling counterargument to memory-editing is not that it’s unnatural or reckless. It’s that we might remove the pain without keeping the wisdom.

In one study at NYU, rats whose fear memories were disrupted no longer avoided dangerous cues. They walked into places where they had once been shocked, oblivious to the threat. When we erase hurt, we erase the part of ourselves that learned how to endure.

A Different Kind of Healing

This isn’t an argument against treatment. For example, PTSD is more than just a memory; PTSD is a nervous system in overdrive, a life paused inside an unrelenting moment. In this case, damping the emotional intensity of those memories is more a form of liberation.

The ethical line appears not at the removal of unbearable pain, but at the removal of meaningful pain, a subtle difference.

So, scientific interventions can help us loosen trauma’s grip, but perhaps they should not offer us amnesia.

What We Stand to Lose

Every once in a while, when I think about memory alteration, I imagine a version of myself who never had to rebuild after loss. Someone lighter, less afraid, unburdened.

But that person would not know why loyalty matters, they would not understand the texture of fear or the softness that follows grief, and they would not know the cost of love. They would be me without the evidence that I have lived.

Maybe the Goal Isn’t Erasure

The goal is not to extract a memory as if it were a stain that can be lifted. Perhaps the goal is to reinhabit it in a new way, so that its emotional weight is redistributed and its meaning evolves rather than disappears. To reshape the experience without erasing the fact that it occurred.

Neuroscience may eventually offer the ability to select what we carry forward. Yet meaning is something we craft through engagement, not something we inherit passively or delete at will. The self grows through reinterpretation, revision, and integration, not through subtraction.

So, Is a Life Without Painful Memory Better?

It might be simpler, or lighter, but what makes a life whole is rarely what makes it easy. Pain itself is not the adversary. What harms us is the sense of being imprisoned by it, unable to move beyond its earliest form.

A life without painful memory may shield us from suffering, but one shaped through painful memory gives rise to everything that matters.

Most of us live somewhere between those two possibilities. We carry moments that hurt but keep learning how to carry them differently. In that ongoing process, memory acts as a teacher, and the self becomes something we build rather than something we escape.

That is where the story, no matter how tragic, ends, and growth begins.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

Frames of Identity

The first impression you give someone feels simple.

A glance, a phrase, the slight tilt of your voice as it tries to decide whether to sound confident or careful. But beneath that moment sits a truth most people never notice. It may be easy forget that others never gain awareness of the full architecture you are. Rather, a moment of awareness is simply one frame in a long sequence, and your brain rushes to stitch these frames together so you can believe there is a solid self living behind your eyes.

Identity is not what we think. I understand it as a continuity the brain desperately creates from separate moments to make sense of the movement of our lives. Neuroscientist Anil Seth calls this a controlled hallucination. The mind fills the gaps so you do not feel the gaps. It connects the flicker of one second to another until the whole thing seems unbroken, like a film reel running just fast enough to appear real.

We like to believe we are consistent people. Yet the research on memory says otherwise. We are creatures of reconstruction. Every remembered version of yourself is edited, packaged for memory, and rearranged. The brain rewrites the story so you can wake up each morning and believe today follows yesterday. This introduces a unique conundrum. Rather than storing identity, we regenerate it every day.

So when someone asks what first impression you want to give, the real question is much, much stranger, and it sounds something like this:

Which version of yourself do you choose to step into the next moment of your life? Which frame do you choose as the doorway?

This is where things shift from science to philosophy. Time feels like a flowing river, but psychologists who study chronostasis suggest that much of time is perception layered on top of uncertainty. The brain inserts its own continuity to prevent us from feeling the world as a collection of tiny, isolated pulses. If we experienced pure discontinuity, we would lose our sense of self within days.

Identity is the story your brain tells so you can stay afloat.

And yet there is something quite beautiful in that. If the self is an invention, it means you are not trapped by whatever story you once believed. You have a say in how the next frame develops. The first impression you offer someone is a creative act rather than a performance. It is the moment you decide which what stays, and what goes.

The poet Ocean Vuong once wrote that memory is a story we carry in order to survive. I think identity is similar. A living thing. An ongoing choice. A narrative held together not by perfect accuracy but by the desire to be understood.

So when someone meets you for the first time, they encounter a glimpse. A soft outline of a self that is always shifting. You might wish people could see the fuller version of you, the one that carries all your experiences and contradictions and small private joys. But this gentle incompleteness is part of what makes human connection meaningful. We meet one another through keyholes. We will never know the full interior, so we stay curious, listening. We keep evolving our impression of each other.

The mind protects us from the terror of a fractured reality by mashing together all the sense-datum we receive each day into something that seems continuous. Our task is just to participate in that creation with care and to let ourselves change while accepting that others will only ever see fragments.

Identity behaves a little like starlight. From a distance you see a single shimmer and assume it is the whole story. If you could travel closer, you would find a roaring furnace made of collisions, and pressure, and centuries of change. The light you see from afar, while seemingly false, is simply the only version that can cross the distance. It gives you a place to aim your attention.

A first impression works the same way. It is the part of you that travels. The part that reaches others first. The person you are is not the glow but the whole constellation of experiences that shaped it. And the self beneath all of that, the one even you struggle to map, is the vast system of forces and history that the mind is still learning to name.

The good thing about all this is that identity does not need to be solved. You do not have to know exactly who you are to live as someone real. You can be in motion, gathering pieces, setting others down, changing shape without warning. For you were never meant to be a statue.

Even scientists who study memory admit that the brain edits and revises and rearranges our story. If the mind keeps rewriting you, then you are allowed to participate in that creation. You are allowed to change your mind about yourself. You are allowed to hold uncertainty without feeling lost.

There is nothing weak about that. There is nothing broken about being unfinished.

Identity is a conversation between what made you and what you choose next. It is a bridge you are always building, even when the blueprint is unclear. The gaps are not failures. The gaps are invitations. They ask you to imagine, to choose, to become.

And maybe that is the real beauty. We are not defined by the parts we cannot explain. Instead, we are defined by the meaning we learn to create from them. Every time you step forward, you add a piece to your ever-growing puzzle. It does not matter if you don’t see the full picture yet, because, truth is, life wasn’t made to make sense from the inside.

So if you feel unfinished, good. It means there is space to grow toward a self that feels honest. It means you still have room for new light. It means the story is unfolding and you are awake inside it.

You are allowed to be a work in progress. You are allowed to be a constellation still forming. You are allowed to discover who you are by living, not by knowing.

And that is enough.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

Why Forgetting Might Be the Most Human Thing We Do

We like to think of memory as proof of who we are. The things we remember become the architecture of our identity, yet beneath that structure lies something quieter, more fragile, and perhaps more vital: the things we forget.

Forgetting has always been treated as the mind’s flaw. A smudge in the lens. But what if it’s the very process that keeps the lens clear?

The Brain’s Gentle Refusal

Neuroscience describes memory as a process of constant revision. The hippocampus stores and reshapes what we take in, then loosens its grip when something no longer serves the present (Squire, 2009).

Researchers in Toronto proposed that the brain forgets to survive. Without that ability, consciousness would collapse under its own weight (Bjork, 1975). We would be unable to tell what matters. The mind that never forgets cannot change its mind.

Every day, thousands of synaptic connections fade, but traces remain as pathways that strengthen when we return to them. The rest dissolve into the white noise of experience, making room for new learning, new meaning, and new selves (Kandel, 2006).

The Poetry of Impermanence

When we revisit a memory, we rewrite it. The scene shifts, colors dull or brighten, dialogue rearranges itself (Loftus, 2005). What we call memory is really imagination tethered to a few truths.

There is something sacred about this impermanence. It protects us from being trapped in yesterday’s version of ourselves. It allows pain to lose its sharpness, allows love to change shape without vanishing. Forgetting is not the opposite of remembering; it is how remembering stays bearable (Hardt, 2008).

A Mind that Learns to Release

To live fully may mean learning to let thoughts fade without resistance. We do not abandon what we forget; we carry the echo of it. The brain understands this long before we do. It edits with care, choosing what we are ready to carry forward (McGaugh, 2000).

Some cultures have long understood this rhythm. The Japanese concept of mono no aware—the bittersweet awareness of impermanence—captures the beauty of forgetting. The ancient Greeks linked memory to Mnemosyne, the mother of the Muses, yet they also revered Lethe, the river of forgetting, as the path to peace (Assmann, 2011).

The self that remembers everything would have no room to grow, and the one who forgets too easily would lose coherence. So we exist between the two in a delicate equilibrium of holding and release.

The Human Art of Letting Go

Forgetting is not a failure of intellect but a condition of grace. It gives us the courage to begin again, to rebuild understanding without the burden of total recall. The mind renews itself in the spaces it empties.

Perhaps this is what it means to be human: to remember just enough to love the world, and to forget just enough to forgive it.

References

Squire, L. R. (2009). Memory and Brain. Oxford University Press.

Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge University Press.

Bjork, R. A. (1975). Retrieval as a memory modifier: An interpretation of negative recency and related phenomena. In J. Brown (Ed.), Recall and Recognition (pp. 123–144). London: Wiley.

Hardt, O., Nader, K., & Nadel, L. (2008). Decay happens: The role of reconsolidation in memory. Trends in Neurosciences, 31(8), 374–380.

Kandel, E. R. (2006). In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind. W. W. Norton & Company.

Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12(4), 361–366.

McGaugh, J. L. (2000). Memory–a century of consolidation. Science, 287(5451), 248–251.

Schacter, D. L. (2001). The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Houghton Mifflin.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

The Zeigarnik Effect: Why Unfinished Tasks Stay in Your Head

I. The Weight of the Unfinished

You open your phone to check one thing. Fifteen minutes later, you’ve replied to two texts, saved a recipe, watched half a video, and somehow never done what you meant to do in the first place. When you finally put it down, your mind still hums with half-formed tasks.

Our brains were never built to live in open tabs.

Psychologists call this the Zeigarnik Effect: the tendency to remember unfinished or interrupted tasks more vividly than completed ones. It’s why a forgotten to-do list nags at you more than the dozens of items you’ve already crossed off. The mind craves closure the way the lungs crave air.

But because our world never truly ends, that craving becomes a quiet torment.

II. The Zeigarnik Effect: The Brain’s Unfinished Symphony

In the 1920s, psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik noticed something curious: waiters remembered unpaid orders better than completed ones. Once the bill was settled, the details seemed to vanish from memory.

Modern neuroscience has since confirmed her insight. Our brains generate dopaminergic tension when something is incomplete, which is a kind of cognitive itch that pushes us toward resolution. Completion relieves the tension, but only for a moment. Soon the mind looks for the next unfinished thing to chase.

The internet runs on this loop. “Next episode” buttons, red notification dots, infinite scrolls, and each one a tiny cliffhanger engineered to keep us suspended in the half-finished.

III. Decision Fatigue: The Cost of Constant Choice

Every unfinished thought competes for energy. Add a thousand small choices, what to wear, text, eat, or watch, and the brain begins to tire. The result is decision fatigue, the invisible tax of modern life.

Research by Roy Baumeister and colleagues shows that every decision draws from the same cognitive pool we use for focus and self-control. As the day goes on, that pool drains.

We call it burnout or lack of motivation, but really it’s just the cost of too many open tabs.

Every half-done task is a leak in the mind’s attention, and we are slowly running dry.

IV. The Digital Age: Infinite Loops, Finite Minds

Our devices have become machines for fragmentation.

Psychologists describe something called cognitive residue, the trace of attention left on a task even after we’ve moved on. Each switch between apps or thoughts leaves behind a faint echo, blurring our focus until nothing feels whole.

This state of half-presence has a name: psychological entropy. It’s the discomfort that arises when the mind’s order dissolves into chaos. Modern media feeds that entropy, keeping us suspended in the tension of what’s next.

In the economy of attention, our unfinished thoughts have become the most valuable commodity.

V. Creativity and the Gift of the Unfinished

Not all incompletion is a curse. The same tension that drives distraction can also spark creativity.

Writers, scientists, and musicians have long relied on the “productive pause”, defined as the act of stepping away to let the subconscious take over. Neuroscience calls this the incubation effect, and it’s tied to the default mode network, the system that activates when we rest, wander, or daydream.

Unfinished ideas incubate. They evolve in silence. They grow roots while we sleep or walk or stare into space.

To pause is to make room for the unseen work of the mind.

VI. The Youth Paradox: Overstimulated and Underslept

For teens and young adults, this cycle is especially intense. School, social media, and constant performance pressure combine into a mental marathon without finish lines. Every notification and assignment becomes another open loop.

This chronic stimulation bleeds into sleep, disrupting the brain’s nightly ritual of sorting, storing, and restoring. During REM and slow-wave sleep, the brain organizes memory, cleanses itself of metabolic waste, and closes the loops we left open during the day.

When sleep is cut short, those loops remain unclosed. We wake up cluttered and foggy in a generation living in mental overdrive yet feeling perpetually unfinished.

We fall asleep simply to tidy the chaos our waking minds cannot.

VII. Closing the Loop: The Art of Choosing Less

The great misconception, especially among the young and ambitious, is that mental toughness means constant motion. In reality, clarity often comes from subtraction.

Choosing less doesn’t equate to caring less. It is just to care more precisely.

We can’t close every loop, nor should we. The goal is to know which ones deserve our attention and which can remain gracefully unfinished. The brain, after all, thrives on both tension and rest. One highly effective habit you can try is to establish some sort of “second brain” for yourself; a notebook, a note-taking app, or a post it that holds all the daily scribbles you realize you must accomplish at some point.

To live deliberately is to choose which threads to tie and which to let drift, trusting that some of life’s most meaningful work happens in the quiet space between.

In a world obsessed with doing more, perhaps the wisest act is simply to finish less, but in doing so, finish more fully.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

How to Rewire Your Brain in the Last 60 Days of 2025

Sixty days left in 2025. That’s enough time to either coast through the end of the year or to reprogram how you think, focus, and act. The truth is, your brain remains remarkably adaptable.

This is not about resolutions. It is about neuroscience and the quiet biological fact that change is built on repetition and reflection.

1. The Myth of the Big Reset

We love the fantasy of transformation: new notebooks, gym sign-ups, the illusion that change begins on command. But real rewiring does not happen that way.

Neuroscience shows growth is not a switch but a slow layering of signals. Every day your brain listens to your behavior and adjusts. Patterns of thought and action, repeated often enough, become automatic pathways. You do not “flip” into a new self. You train your neurons into one.

Mindset shift: Stop thinking in resolutions. Start thinking in repetitions.

The 1% Rule

Improve by one percent each day – one percent more focus, one percent more rest, one percent more presence. After sixty days, that is not sixty percent improvement. Compounded, it is exponential. Neural networks strengthen with consistency, not drama.

2. The Science of Rhythm: Finding Your Neural Schedule

Your perfect day is already coded into your biology. The brain runs on circadian (daily) and ultradian (hourly) rhythms that govern alertness, creativity, and fatigue. Ignoring those rhythms is like rowing against a current: possible, but exhausting.

The Focus Framework

- Track your natural peaks for three days. Note when your brain feels sharpest and when it fogs.

- Protect your high-focus window for deep work – writing, studying, thinking.

- Use low-focus hours for logistical tasks and errands.

- Rest every 90 minutes to align with attention cycles and help neurotransmitters reset.

Once you align your schedule to your neural rhythm, productivity will come more easily, not just from sheer willpower.

3. The Novelty Principle: Reawakening Dormant Circuits

The brain thrives on surprise. Novelty (new experiences, ideas, or environments) activates dopamine pathways tied to curiosity and learning. When everything feels repetitive, the brain goes into predictive mode and attention fades.

Novelty is not merely entertainment. It is biological nutrition for attention.

Small Ways to Add Novelty

- Change your study or commute route.

- Read an author or genre you rarely choose.

- Listen to a podcast outside your usual subjects.

- Rearrange your workspace or swap your morning routine.

Each small disruption forces your sensory and motor cortices to re-coordinate, for more whimsy in life.

4. The Attention Economy and the Art of Recovery

Your attention is your most limited neural currency. Every task switch or phone check spends dopamine and glucose, the fuels of focus. Constant context switching leads to micro self-interruption that accumulates fatigue.

The Two-Window Method

- Deep Work Window: One 90-minute period daily for immersion. One task, zero notifications.

- Restorative Window: 20 minutes of real rest after deep work: walking, breathing, or silent reflection. No screens.

During rest, your brain consolidates learning.

5. Sleep: The Night Shift of the Brain

Sleep is not optional. During deep sleep, brain cleaning processes remove metabolic waste. During REM sleep, emotional and sensory memories get integrated into long-term patterns.

The Rewind Ritual

- Thirty minutes before bed, dim lights and screens.

- Write three lines about what you learned or noticed today.

- Visualize your brain sorting and storing those experiences overnight.

After sixty days, this simple ritual strengthens hippocampal memory consolidation and emotional balance.

6. The Emotional Brain: Reframing Stress

Stress in small doses sharpens focus and motivation; chronic stress is what harms the brain. The trick is to reframe stress as signal, not threat.

The Stress Reframe

- Name it: say to yourself, “My body is preparing me.”

- Breathe in for four counts, out for six to activate the calm response.

- Turn the task into curiosity: ask, “What is this trying to teach me?”

This practice trains the prefrontal cortex to interpret pressure as stimulation. Over time, that narrative becomes automatic and resilience grows at the circuit level.

7. Reflection: The Architecture of Identity

Your brain learns not only from action, but from what it notices about action.

The Nightly Check-In

- What did I learn today about the world or about myself?

- What felt meaningful?

- What drained me, and why?

- Who made me smile?

Five minutes of nightly journaling rewires self-awareness. You begin to see patterns in the quiet beginning of self-creation.

8. The 60-Day Framework for Lasting Change

Use this structure to make the final sixty days of 2025 transformative without theatrics or burnout.

| System | Action | Neural Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | One 90-minute deep work block daily | Strengthens prefrontal control |

| Recovery | 20-minute restorative break | Resets dopamine and consolidates learning |

| Sleep | Consistent bedtime and Rewind Ritual | Enhances memory and mood stability |

| Novelty | One new experience weekly | Activates neuroplasticity |

| Reflection | 5-minute nightly journaling | Strengthens self-awareness circuits |

9. The Quiet Revolution

When the year ends, the world may look the same. But beneath the surface, your brain will have changed. You will return to focus faster. You will respond to stress with more equanimity. You will notice life more clearly.

That is the real miracle of the human brain: it is always becoming. And sixty days is enough time to begin again.

You got this. Now take the steps, no matter how small, and finish the year strong.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

Ingredients for Your Perfect Day, Backed by Neuroscience

Your perfect schedule is already built in to your brain, here’s how to find it.

Ever wonder what a perfect day would look like if your brain actually cooperated? As a student, I’ve spent countless mornings staring at my planner, wondering how to get everything done without going crazy. Between lectures, homework, and the never-ending influx of notifications, it often feels impossible to stay focused or energized. Luckily, neuroscience has some surprisingly practical answers, tools and insights you can actually use to design a day that works with your brain, not against it.

Sleep: The Non-Negotiable Starter

Your neurons are night-shift workers. They do not take coffee breaks. Deep sleep is when your brain consolidates memory, prunes connections, and basically declutters itself. Skipping it is like trying to run your laptop with twenty tabs open and battery at 10%. For students, this means late-night cramming is usually self-defeating. Your brain might get the homework done but it will forget half of it by tomorrow. I know it’s hard, but please aim for 7-9 hours and try to stick to a consistent schedule. Your future self will thank you.

Timing Matters

Your brain does not operate at full power all day. For most people, mornings are best for focus-heavy tasks like writing essays or solving math problems. Afternoons are better for lower-stakes or social tasks because your alertness naturally dips. Evenings, surprisingly, are when creativity peaks, making it the perfect time for brainstorming, art, or revising your philosophy blog. Mapping your most important tasks to your brain’s natural rhythms is like scheduling meetings with your most demanding client, which happens to be yourself.

Work in Bursts

Attention is a finite resource. The brain has ultradian rhythms, cycles of about 90-120 minutes of high alertness followed by a dip. Working for long stretches without a break is like driving a car without refueling. Try focusing for 25-50 minutes, then take a 5-10 minute break. Walk around, stretch, or just stare out the window. Your neurons actually perform better when given a pit stop.

Tiny Wins and Dopamine

Dopamine is the brain’s reward molecule. It helps you pay attention, remember things, and feel good while doing them. Checking your phone releases dopamine, which is why it’s so addictive. You can hack the system by rewarding yourself for small accomplishments. Finish a paragraph or send an important email, then treat yourself to a song or a snack. These micro-rewards keep motivation high without falling into the trap of procrastination disguised as productivity.

Flow Is Your Friend

Contrary to popular belief, your brain cannot multitask. It can only switch attention quickly, leaving a trail of incomplete thoughts. Flow happens when your skill level matches the challenge in front of you. That sweet spot where time disappears is the perfect zone for productivity. Batch similar tasks, eliminate notifications, and dive in without guilt. Flow loves focus, and your brain will thank you with higher quality work and less stress.

Move Your Body

Even a 10-minute walk or a few stretches trigger brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. This protein helps neurons grow and stay flexible. Movement literally helps your brain work better. Try walking to class, stretching between study sessions, or even dancing in your room. It’s scientifically proven to reduce stress while boosting energy.

Reflect and Reset

Reflection is where your brain consolidates memory, processes mistakes, and primes itself for tomorrow. Journaling, meditating, or just mentally replaying the day helps you learn from experience. 5 minutes of reflection at the end of the day can provide actionable insights and make tomorrow feel a little less chaotic.

The Takeaway

A perfect day is not about cramming more hours into your schedule or pretending to be a productivity robot. It is about designing your environment, your tasks, and your mindset around how your brain actually works. Sleep, flow, movement, timing, rewards, and reflection are the ingredients. Layer them thoughtfully and your day becomes less of a struggle and more of a rhythm. With a little planning and a lot of understanding of your own brain, students (like you and me) can actually make each day feel productive, energizing, and maybe even a little magical.

You got this! Now go take the steps, no matter how small, to achieve your goals!

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.

The Night Shift: How Your Brain Works Overtime While You Dream

You clock out. Your brain clocks in.

Every night, while the world fades into quiet, your brain gets to work. Far from idle, it runs a shift that scientists are still trying to understand: sorting, repairing, and processing the fragments of the day into something coherent.

The Science of Sleep and Memory

Sleep is not passive rest. It’s a complex biological process with stages as distinct as scenes in a film. During slow-wave sleep (SWS), the brain replays recent experiences, transferring short-term memories from the hippocampus to the neocortex (Rasch & Born, 2013). This “neural replay” consolidates learning, preserving only what matters most and pruning what doesn’t.

Then comes REM sleep, where neurons fire in irregular bursts, the amygdala lights up, and logic takes a backseat. This is the stage of vivid dreaming, where emotions, creativity, and subconscious processing take center stage. REM doesn’t just solidify memories; it integrates them, connecting new information with old to form insight (Walker & Stickgold, 2010).

In short, your dreams might be your brain’s way of telling stories about who you’re becoming.

Why Dreams Feel So Real

During REM, the brain’s prefrontal cortex, responsible for logic and self-awareness, quiets down. Meanwhile, visual and emotional centers fire intensely, creating immersive experiences that feel convincing even as they defy physics. This is why you can fly, cry, or argue with someone who doesn’t exist.

Neurologically, dreams may serve as emotional regulation. They allow us to revisit unresolved experiences in a safe mental space. Matthew Walker calls it “overnight therapy,” where the brain softens emotional edges while preserving the memory itself (Walker, 2017).

When the Night Shift Is Cut Short

The problem is that modern life interrupts this process. Teens and young adults (like me), those who need deep sleep most, are sleeping less than ever. Tell me about it. School starts early, screens glow late, and the myth of productivity glorifies being tired by giving your all every day. Yet chronic sleep deprivation can reduce hippocampal function, impair decision-making, and weaken emotional control (Curcio et al., 2006).

Without enough REM and deep sleep, the brain’s night shift never finishes its work, resulting in fuzzier memories, mood swings, and a subtle sense of disconnection.

What It Means for Young Minds

For high schoolers and college students, sleep is often treated like a luxury, not a necessity. But neuroscience argues the opposite. The hours you spend asleep aren’t wasted. They’re when your brain learns and grows. Every dream, no matter how strange, reflects a network of neurons trying to make sense of you and your world. And there are so many more benefits outside of what sleep does to your brain that should be emphasized.

The takeaway isn’t to chase every dream for meaning. It’s to respect the process that creates them. Let your brain do its night shift. Turn off the lights. Trust that in the quiet, it’s still working. Because it is organizing, remembering, and rebuilding who you’ll be when you wake.

References

Curcio, G., Ferrara, M., & De Gennaro, L. (2006). Sleep loss, learning capacity, and academic performance. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10(5), 323–337.

Rasch, B., & Born, J. (2013). About sleep’s role in memory. Physiological Reviews, 93(2), 681–766.

Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2010). Overnight alchemy: Sleep-dependent memory evolution. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(3), 218–226.

Walker, M. P. (2017). Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner.

Written by Mason Lai, a high schooler from California who wishes he let his brain do the night shift more.

In Sync: How Music Aligns Our Brains and Binaural Beats

There is a strange calm that washes over you when lo-fi beats fill your headphones while studying. There is an unspoken connection in a crowded concert hall when thousands sway together. These experiences are more than just beautiful; they are neural. Music has the power to synchronize brain activity within and across individuals, aligning thoughts, emotions, and attention in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Neural Synchronization

Neuroscientists call this neural synchronization. When your brain hears a beat, its neurons start to oscillate in rhythm with it. Note that this is not just happening in your auditory cortex; it spreads to motor regions, the cerebellum, and prefrontal areas involved in focus and expectation.

Even more fascinating, people listening to the same music often show inter-brain synchrony. Studies reveal that their brainwaves can match up in time and frequency, creating a subtle shared experience of connection (Lindenberger et al., 2009; Sänger et al., 2012). In a very real sense, music can make our minds move together.

Binaural Beats & the Brain’s Rhythmic Flexibility

Neural sync isn’t just for concerts. Binaural beats use two slightly different tones, one in each ear, tricking the brain into hearing a third, imagined beat. This auditory illusion can nudge your brain into different rhythms, from alpha waves that calm you to beta waves that sharpen your focus (Lane et al., 1998; Goodin et al., 2012).

Listening to binaural beats in specific frequency ranges can modulate brain states. Alpha-range beats (8–12 Hz) are associated with relaxation, while beta-range beats (13–30 Hz) may enhance focus or alertness (Lane et al., 1998; Goodin et al., 2012). While research is still exploring the effects, the principle is simple: our brains are rhythm machines, and sound is a powerful conductor.

Why It Matters

When our brainwaves align with others through shared sound, the boundaries of self and other blur. The same mechanisms that allow a drummer to keep time also underlie the neural foundations of empathy and cooperation. It explains why music feels social even in solitude. When our neurons align with rhythm, whether in a concert, a quiet practice session, or through binaural beats, we experience a sense of belonging.

Music organizes our inner worlds and aligns them with others, proving that even when we’re alone, our brains are seeking resonance.

References

Garcia-Argibay, M., Santed, M. A., & Reales, J. M. (2019). Efficacy of binaural auditory beats in cognition, anxiety, and pain perception: A meta-analysis. Psychological Research, 83(2), 357–372.

Goodin, P., Wildermuth, L., & Sumners, C. (2012). Binaural beat audio and cognitive performance: A review of the evidence and potential mechanisms. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 44.

Lane, J. D., Kasian, S. J., Owens, J. E., & Marsh, G. R. (1998). Binaural auditory beats affect vigilance performance and mood. Physiology & Behavior, 63(2), 249–252.

Large, E. W., & Snyder, J. S. (2009). Pulse and meter as neural resonance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169(1), 46–57.

Lindenberger, U., Li, S.-C., Gruber, W., & Müller, V. (2009). Brains swinging in concert: Cortical phase synchronization while playing guitar. BMC Neuroscience, 10, 22.

Oster, G. (1973). Auditory beats in the brain. Scientific American, 229(4), 94–102.

Sänger, J., Müller, V., & Lindenberger, U. (2012). Intra- and interbrain synchronization and network properties when playing guitar in duets. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 312.

Trainor, L. J., & Cirelli, L. (2015). Rhythm and interpersonal synchrony in early social development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337(1), 45–52.

Zatorre, R. J., Chen, J. L., & Penhune, V. B. (2007). When the brain plays music: Auditory–motor interactions in music perception and production. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(7), 547–558.

The Neuroscience of Decision Fatigue: Why Choosing Dinner Feels Impossible Sometimes

You open the fridge, determined to make something healthy. Ten minutes later, you’re staring at leftovers, wondering if cereal counts as dinner.

It’s not laziness or indecision, it’s biology. Every choice you make throughout the day, from what to wear to which email to answer first, draws from a limited supply of mental energy. By evening, your brain is running on fumes.

This invisible drain, known as decision fatigue, reveals something fascinating about how the human brain works. At it’s core, decision fatigue is not a failure of willpower but a natural consequence of how our neurons process choices. The problem is that modern life was not built with that biology in mind.

Understanding decision fatigue is not simply about improving productivity; it is about recognizing the biological limits of human cognition in a world that demands constant engagement.

The Brain’s Energy Economy

The human brain weighs roughly three pounds but consumes nearly 20% of the body’s energy at rest (Raichle & Gusnard, 2002). Most of this energy supports synaptic activity, which is the electrochemical communication between neurons we need for thought and judgement.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions such as reasoning and self-control, is particularly energy-intensive. When glucose levels decline in this region, the brain’s capacity for self-regulation and decision-making drops sharply (Gailliot et al., 2007). Neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman describes this as a “neural budget” that depletes with use. Neural budget is a concept that many struggle with because they believe willpower will be enough for difficult tasks and maintaining drive throughout extended periods.

Every choice, even trivial ones like selecting a meal, engages these same neural pathways. As the day progresses, neurons in the prefrontal cortex communicate less efficiently, and the brain shifts from deliberate reasoning to what psychologists call heuristic processing, defined as simpler, faster decision-making strategies (Kahneman, 2011).

The Psychology of Overchoice

Furthermore, modern environments amplify this biologically induced limit of decision-making capacity. Psychologist Barry Schwartz famously described this as “The Paradox of Choice”. Essentially, the more options we face, the more anxious and dissatisfied we become (Schwartz, 2004).

Research at Stanford University found that individuals confronted with extensive choices, such as 24 flavors of jam, were significantly less likely to make a purchase than those offered only six options (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). Each additional alternative increases cognitive load and prolongs the decision process, drawing more energy from an already taxed brain.

Unlike physical exhaustion, decision fatigue builds invisibly. It often manifests as irritability, procrastination, or emotional numbness. These are the quiet symptoms of a brain that has simply made too many choices.

The Dopamine Trap

Dopamine, the neurotransmitter responsible for motivation and reward, also plays a role in this cycle. Each decision completed, no matter how small, triggers a small release of dopamine, reinforcing the behavior (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015). But when the brain faces an unrelenting stream of micro-decisions (for me, notifications, texts, playlists, which task to start first), its dopamine system becomes desensitized.

This desensitization blurs the line between meaningful and trivial choices, flattening emotional reward and leaving us less motivated. Satisfaction flatlines to dull routine, an effect researchers call hedonic adaptation (Brickman & Campbell, 1971). Thus, even enjoyable activities, like choosing what to eat out, begin to feel burdensome.

Modern Life as a Cognitive Overload Experiment

From an evolutionary perspective, the human brain evolved for scarcity, not abundance. Early humans only had to make a few high-stakes decisions per day: when to hunt, where to seek shelter, whom to trust. But today, an average person makes hundreds of decisions before noon. (Albeit not very high-stakes ones, but we are fooled into believing that they are.)

Cognitive neuroscientist Daniel Levitin argues that “each shift in attention sets off metabolic processes that deplete the brain’s neural resources.” (Levitin, 2014) In essence, the constant switching of modern life between countless microtasks induces a continuous state of mental taxation.

Modernity, then, has become a sort of cognitive overload experiment with us as the subjects. As a result, we are fatigued, less creative, less empathetic, and less patient overall. Our higher-order cognition is becoming subtly eroded.

The Case for Cognitive Minimalism

Emerging research suggests that the antidote to decision fatigue is not more efficency, but fewer choices. Cognitive minimalism, the deliberate simplification of daily decisions, conserves neural energy for more meaningful cognitive work (Goyal et al., 2018).

Small interventions, such as automating low-stakes tasks, like Einstein or Steve Jobs wearing the same outfits every day, can significantly reduce cognitive load. This aligns with neural conservation theory: the idea that the brain strategically limits effort to preserve long-term function (Kurzban et al., 2013).

Conclusion: When Simplicity Becomes Intelligence

In popular culture, especially among teenagers and young adults, mental endurance is often glorified as a sign of strength. The ability to “push through” fatigue, multitask endlessly, and make rapid decisions is frequently mistaken for resilience. Yet neuroscience paints a different picture.

Decision fatigue is more than a productivity challenge; it is a reflection of how our cognitive systems evolved. The mechanisms that once helped us survive now collide with an environment of endless stimulation.

This misunderstanding matters. Many young people internalize the idea that slowing down is a weakness, that stepping back means falling behind. In reality, the opposite is true. Rest, constraint, and deliberate choice are not escapes from mental rigor but expressions of it. Each time we choose less, whether by limiting options, simplifying routines, or pausing before the next decision, we conserve cognitive energy and restore clarity.

Ultimately, the neuroscience of decision fatigue reveals an overlooked truth: wisdom is not measured by how much we do, but by how thoughtfully we choose what to do next.

References

Berridge, K. C., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646–664.

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. Adaptation-level theory, 287–302.

Gailliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., et al. (2007). Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(2), 325–336.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M. S., et al. (2018). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kurzban, R., Duckworth, A., Kable, J. W., & Myers, J. (2013). An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(6), 661–726.

Levitin, D. J. (2014). The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload. Dutton.

Raichle, M. E., & Gusnard, D. A. (2002). Appraising the brain’s energy budget. PNAS, 99(16), 10237–10239.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. HarperCollins.

Written by Mason Lai, a student researcher exploring the intersection of neuroscience, psychology, and modern life. Passionate about translating complex ideas into clear, human insights.

How Multitasking Is Rewiring Your Brain (And Not in a Good Way)

Think multitasking makes you more productive? Think again. Here’s how switching between tasks is rewiring your brain, lowering focus, and raising stress (and how you can fix it, too).

Let’s be honest.

You probably have five tabs open right now. Maybe a podcast is playing in the background. Maybe you’re half-texting someone.

It feels like you’re getting a lot done, right? Like you’re maximizing your time.

But here’s the truth: multitasking isn’t helping you. It’s actually training your brain to lose focus, remember less, and crave constant distraction.

Let’s unpack that quickly.

The Multitasking Myth

You’re not really multitasking. You’re task-switching. Every time you jump from one thing to another, your brain has to pause and reset.

Those tiny switches might only take a second, but they add up. Research shows that constant task-switching can slash productivity by up to 40%.

It’s like trying to run a marathon while stopping to tie your shoes every ten seconds.

What It’s Doing to Your Brain

Here’s where it gets wild. Multitasking physically changes your brain.

- Less gray matter: Brain scans show that people who multitask a lot have less gray matter in the part of the brain responsible for focus and emotional control.

- Worse memory: You’re training your mind to chase what’s new instead of digging deep into what matters.

- More stress: Jumping between tasks keeps your brain in “fight or flight” mode. Cortisol (your stress hormone) stays high, and that drains your energy fast.

So yes, multitasking might make you feel busy, but it’s also reshaping your brain in ways that make it harder to focus later.

How To Reboot Your Focus

Good news is, your brain can rewire itself back.

Try these simple fixes:

- Do one thing at a time. Close your extra tabs. Finish a task completely before moving to the next one.

- Batch your distractions. Set times to check texts or emails instead of reacting all day long.

- Practice deep work. Start with 20 minutes of uninterrupted focus. Add time as your brain adjusts.

- Let yourself be bored. Boredom isn’t bad. It’s where creativity and clarity show up.

The Bottom Line

Multitasking isn’t a badge of honor. It’s a brain trap.

The more you split your attention, the more your brain adapts to distraction.

If you want to think clearly, remember more, and actually finish what you start, then do one thing at a time.

Your brain will thank you later.

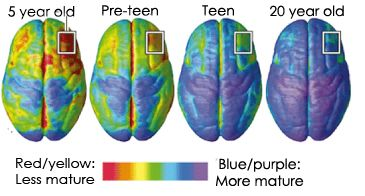

When Does Your Brain Become an Adult?

I’m Not (Yet). But My Brain Is Growing Into Adulthood

When was the first time I truly felt like a grown-up?

Honestly? I haven’t. Not fully. I’m a high school senior — standing on the edge of adulthood, but not quite there yet.

What Does It Even Mean to “Feel Like a Grown-Up”?

Is it about knowing exactly what you’re doing?

If so, I’m not sure anyone ever really knows.

Maybe it’s about handling life’s challenges calmly, making decisions confidently, or feeling in control.

But the truth is that our brains aren’t wired to feel “adult” just because we’ve hit a certain age.

The Brain Doesn’t Care About Legal Milestones

Legally, adulthood starts at 18 or 21, depending on where you live.

Culturally, some say adulthood begins at 30. Some say earlier.

But neuroscience tells a much more nuanced story.

The Prefrontal Cortex: Your Brain’s CEO

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is like the CEO of your brain.

It manages:

- Impulse control

- Emotional regulation

- Long-term planning

- Understanding others’ perspectives

- Managing stress and discomfort

But here’s the thing:

The PFC doesn’t fully mature until your late 20s or even early 30s.

Even more importantly, it’s not just the PFC on its own. We need to factor in how well it communicates with emotional centers like the amygdala that keeps improving well into adulthood (Casey, Tottenham & Liston, 2005).

Why Don’t I Always Feel Like an Adult?

Because feeling like an adult isn’t about your age or your achievements.

It’s about your brain’s wiring and how your mind manages emotions and decisions.

What Happens When You Do?

Neuroscientifically speaking, it’s when your prefrontal cortex takes the lead and calms your amygdala in a process known as top-down regulation.

This means you regulate your own emotional response, which allows you to be fully present and supportive.

Dr. Dan Siegel calls this vertical integration: when higher brain functions sync harmoniously with emotional and physiological systems, creating balance and resilience.

This also ties into the dual-systems theory, which explains the balance between our fast, emotional “hot” brain and slower, thoughtful “cool” brain.

Adulthood Is a Process, Not a Moment

There are no fireworks or instant transformation.

Neurologically, adulting is about:

- Neural integration — brain circuits learning to communicate and cooperate better.

- Flexibility under pressure — choosing thoughtful responses over impulsive reactions.

- Emotional presence — staying grounded even when things get tough.

The Takeaway

I’m not fully grown-up. Maybe you aren’t either.

Sometimes, my brain does act like it’s ready.

And these quiet, uncelebrated moments are proof that adulthood is less a destination and more a gradual, ongoing process.

References

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are.

Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., & Liston, C. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110.

Santa Claus of the Sea: Rethinking Aging Through Surf Therapy

One morning during a quiet surf session, one man stood out from the rest. He had a long, white, Gandalf-esque beard that dripped with seawater. Despite being more than 65 years old, he took waves with a grace that could only be mastered with years of his craft. And from that moment on, he was known to me as the legendary Santa Claus of the Sea.

He was graceful. But this image stands in stark contrast to the current dominant narrative of aging.

The Reality of Aging: Physical and Psychological Ailments

Many health professionals are familiar with the list of common aging-related challenges, including:

- Sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss)

- Impaired balance and proprioception

- Increased risk of falls and fractures

- Joint degeneration

- Reduced cardiovascular endurance

Alongside these physiological changes, we see a rise in mental health challenges:

- Social isolation

- Depression

- Loss of autonomy and identity

- Cognitive decline

These factors compound each other. For example, a loss of balance leads to a fall, which results in injury, which leads to hospitalization, immobility, and sometimes institutionalization, which all accelerate decline.

Modern rehabilitation techniques try to interrupt this cycle, but traditional therapy methods, particularly in geriatric care, often rely on repetitive, low-engagement exercises: resistance bands, parallel bars, leg lifts in clinics. These are essential in many cases, but they’re not enough. My grandma was prescribed chair exercises, but I want her to be able to strengthen herself in practical ways.

Adherence is a chronic challenge. Motivation wanes. And much too often, patients disengage.

So what if we reframed therapy? What if we made it joyful?

Surf and Ocean Therapy: Reconnecting Mind, Body, and Environment

Surf therapy is a movement-based, nature-integrated intervention that merges physical rehabilitation with emotional renewal.

It may sound radical, even niche, but it can gain traction for good reason.

Surfing involves:

- Dynamic balance — reacting to ever-changing surfaces

- Core and limb strength — paddling, popping up, stabilizing

- Coordination and reaction time — reading waves, adjusting positions

- Cardiovascular exertion

- Mental presence — engaging with unpredictability in real time

All of this takes place in a natural environment that stimulates the senses and evokes meaning: the ocean. The ocean is something that soothes the mind, the beach a bonding place for communities, and the water something that reminds people — especially older adults — that they are still capable and evolving.

Evidence Supporting Surf Therapy for Older Adults

Though still an emerging field, several pilot programs and studies are showing promising results — not only for youth and veterans, but also for older adults and people living with chronic conditions.

A few key findings:

- Balance & Mobility: A 2019 study on ocean-based activities for older adults found significant improvements in static and dynamic balance over 12 weeks. Gains persisted at a 3-month follow-up.

- Mood & Depression: Programs like Waves for Change and Ocean Therapy for Veterans report measurable decreases in depression and anxiety after just 4–6 weeks of sessions.

- Social Connection: Group surf sessions foster community — essential for reducing isolation, a major risk factor for early mortality.

- Self-Efficacy: Participants describe a new identity: not as “patients,” but as athletes, learners, or adventurers.

In this way, movement that is meaningful is more sustainable than movement that is merely prescribed.

“But Is It Safe?” — Managing Risks with Realism and Responsibility

“Isn’t surfing dangerous for older adults?”

Yes — and no.

All physical activity carries some level of risk. But so does inactivity.

In fact, sedentarism is one of the most dangerous behaviors for aging adults, associated with:

- Heart disease and stroke

- Type 2 diabetes

- Depression

- Cognitive decline

- Frailty and loss of independence

Surf therapy programs reduce risk by including:

- Soft-top boards and padded equipment

- Shallow-water options and beach-based sessions

- Certified adaptive surf instructors

- Physical therapists on-site or in collaboration

- Buoyancy aids and wetsuits

- Environmental checks (tides, weather, currents)

- Gradual progression, from tide pool to open ocean

Most participants start slowly: learning to float, sit on the board, or wade safely. Athleticism isn’t required. Just reconnecting with movement, shedding fear of it, and being open to growing from unfamiliar experiences.

Surf therapy doesn’t replace traditional rehab. It complements it by giving people a reason to get stronger. And even if it’s not surfing specifically, being outside and in the elements is the reward in it of itself.

Beyond the Clinic: Reimagining Geriatric Therapy

The big idea is this:

Therapy doesn’t have to feel like therapy.

It can feel like joy. Like renewal. Like living again.

Healthy movement shouldn’t be limited to lifelong athletes. The myth that older adults are fragile, disinterested, or unwilling is just that — a myth.

The Santa Claus of the Sea isn’t just a surfer. He’s a living contradiction to our ageist expectations.

So understanding that movement if life at any age, we must devise better plans for maintaining movement in seniors. And we can start by inviting more of our elders into the water.