We like to think of memory as proof of who we are. The things we remember become the architecture of our identity, yet beneath that structure lies something quieter, more fragile, and perhaps more vital: the things we forget.

Forgetting has always been treated as the mind’s flaw. A smudge in the lens. But what if it’s the very process that keeps the lens clear?

The Brain’s Gentle Refusal

Neuroscience describes memory as a process of constant revision. The hippocampus stores and reshapes what we take in, then loosens its grip when something no longer serves the present (Squire, 2009).

Researchers in Toronto proposed that the brain forgets to survive. Without that ability, consciousness would collapse under its own weight (Bjork, 1975). We would be unable to tell what matters. The mind that never forgets cannot change its mind.

Every day, thousands of synaptic connections fade, but traces remain as pathways that strengthen when we return to them. The rest dissolve into the white noise of experience, making room for new learning, new meaning, and new selves (Kandel, 2006).

The Poetry of Impermanence

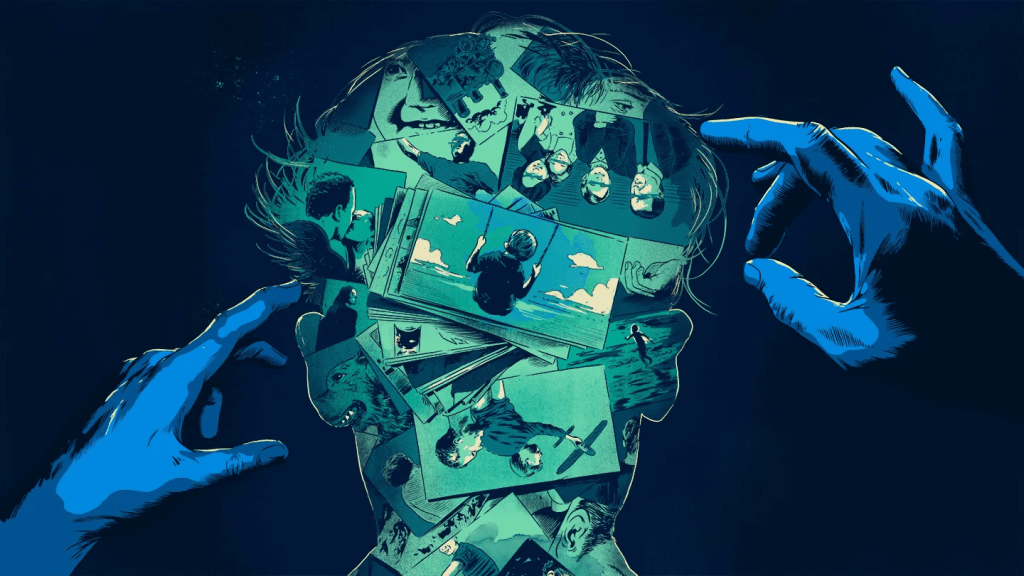

When we revisit a memory, we rewrite it. The scene shifts, colors dull or brighten, dialogue rearranges itself (Loftus, 2005). What we call memory is really imagination tethered to a few truths.

There is something sacred about this impermanence. It protects us from being trapped in yesterday’s version of ourselves. It allows pain to lose its sharpness, allows love to change shape without vanishing. Forgetting is not the opposite of remembering; it is how remembering stays bearable (Hardt, 2008).

A Mind that Learns to Release

To live fully may mean learning to let thoughts fade without resistance. We do not abandon what we forget; we carry the echo of it. The brain understands this long before we do. It edits with care, choosing what we are ready to carry forward (McGaugh, 2000).

Some cultures have long understood this rhythm. The Japanese concept of mono no aware—the bittersweet awareness of impermanence—captures the beauty of forgetting. The ancient Greeks linked memory to Mnemosyne, the mother of the Muses, yet they also revered Lethe, the river of forgetting, as the path to peace (Assmann, 2011).

The self that remembers everything would have no room to grow, and the one who forgets too easily would lose coherence. So we exist between the two in a delicate equilibrium of holding and release.

The Human Art of Letting Go

Forgetting is not a failure of intellect but a condition of grace. It gives us the courage to begin again, to rebuild understanding without the burden of total recall. The mind renews itself in the spaces it empties.

Perhaps this is what it means to be human: to remember just enough to love the world, and to forget just enough to forgive it.

References

Squire, L. R. (2009). Memory and Brain. Oxford University Press.

Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge University Press.

Bjork, R. A. (1975). Retrieval as a memory modifier: An interpretation of negative recency and related phenomena. In J. Brown (Ed.), Recall and Recognition (pp. 123–144). London: Wiley.

Hardt, O., Nader, K., & Nadel, L. (2008). Decay happens: The role of reconsolidation in memory. Trends in Neurosciences, 31(8), 374–380.

Kandel, E. R. (2006). In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind. W. W. Norton & Company.

Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12(4), 361–366.

McGaugh, J. L. (2000). Memory–a century of consolidation. Science, 287(5451), 248–251.

Schacter, D. L. (2001). The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Houghton Mifflin.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.