How instinct and intuition shape us, and how the nervous system allows us to rewrite our oldest impulses

We usually imagine instinct as something permanent, a force that precedes thought and resists revision, moves faster than reason, feels older than memory, and often arrives before we have a chance to interpret it.

A sudden flinch, a tightening in the chest, a hesitation in front of a crowd; these are signals from biology’s first draft of the self.

Intuition, by contrast, feels learned yet inexplicable. It is judgment from experience, from patterns we have absorbed but cannot fully articulate. The distinction seems clear: instinct is inherited, intuition is acquired. Yet according to neuroscience, they are closer than meets the eye.

I. Instinct as the First Draft

Neuroscience shows that instinctive circuits through the amygdala, periaqueductal gray, and other subcortical structures operate at speeds that bypass conscious thought (LeDoux, 1996) in order to guide us toward survival. Instinct carries ancient wisdom, but it is not absolute, and in modern life some consider it an outdated architecture.

Instinct can change. Neuroplasticity allows the nervous system to reshape itself in response to experience, so emotional memory can be updated each time it is recalled in a process called reconsolidation (Phelps et al., 2009). Fear responses once thought permanent can be weakened through repeated exposure. Prosocial impulses can be reinforced through practice.

II. Intuition as the Brain’s Ongoing Revision

Intuition is the mechanism through which these revisions emerge through pattern recognition: the brain compressing thousands of experiences into a single instant of guidance.

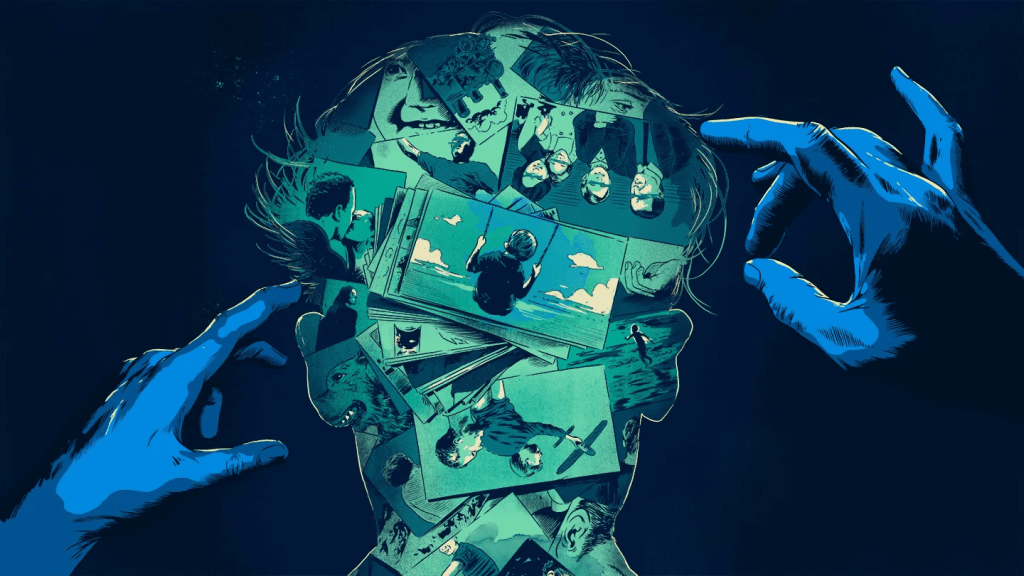

A seasoned firefighter senses a building is unsafe before assessing the evidence. A guitarist feels the right chord before theory explains it. These are instincts refined by experience and practice.

The distinction between instinct and intuition fades because both rely on the nervous system’s ability to encode and adapt information. What feels immediate is often the negotiation between our ancient foundations and modern experience.

III. Rewriting Instinct and the Responsibility of Freedom

The possibility of rewriting instinct raises ethical and philosophical questions. If our deepest reactions can be altered, we bear responsibility for which impulses we cultivate. If courage can be trained, empathy practiced, fear tempered, then nothing stops us from imagining “ideal” humans—creatures optimized for rationality, cooperation, or moral virtue. History brings up a cautionary lens. Communism and socialism were once heralded as systems that could perfect society, yet the unpredictability of human behavior and the complexity of the world made total control impossible. Even carefully designed utilitarian experiments struggle to account for the emergent consequences of individual choices and the infinite ways context shapes action.

Maladaptive environments, however, can carve unhealthy patterns into the nervous system just as easily. The plasticity of instinct is both liberating and fragile. It allows us to grow, but it is also inevitably shaped by forces outside conscious control. In this sense, instinct is less a fixed verdict than ongoing revision. Human potential will perhaps always remain uncertain. We cannot manufacture perfection, yet we can still strive. So, the work of shaping instinct cannot be absolute; rather it fluctuates between what can be trained and what must be lived.

IV. Living Between Draft and Revision

Instinct is the prewritten framework of the self, a set of impulses we inherit before we can interpret them. Intuition layers experience atop it, shaping quiet guidance we rarely notice. Conscious attention is the instrument of our change, refining and redirecting without ever fully controlling the story.

Reflex can become deliberate as reaction can become understanding. We are neither prisoners of our earliest wiring nor masters of its total rewriting.

Rewriting instinct carries ethical weight. If courage, empathy, or fear can be trained, shaping the impulses of others through education, culture, or biotechnology is imaginable. History reminds us that attempts to “perfect” humans or societies fail, as the world resists total control. Yet this imperfection also carries hope: the same plasticity that allows harm also allows care, reflection, and responsible guidance.

To trust instinct is to honor its voice while recognizing limits. To engage thoughtfully is to co-author the self. Living fully must mean navigating the tension between inherited and cultivated impulses, letting both guide us. But this responsibility extends beyond personal growth. How we train instinct shapes the ethical contours of who we become. Courage cultivated in adolescence can influence moral choices in adulthood. Empathy reinforced through social experience alters how we respond to strangers. Fear tempered through exposure can prevent harmful overreactions. Shaping instinct means editing our identity. The ethical dimension is unavoidable: the self is inseparable from the impulses we refine, and the values we choose to embed in them.

References

- LeDoux, Joseph. The Emotional Brain. 1996

- Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 2011

- Damasio, Antonio. Descartes’ Error. 1994

- Phelps, Elizabeth et al. Nature, 2009

- Sapolsky, Robert. Why Zebras Do Not Get Ulcers. 1994

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.