Pixar’s Inside Out is often praised for making emotions legible, by color-coding them, naming them, and placing them neatly at their respective spots at a control panel. While it may be easy to watch the movie and believe its message is the value of emotional mastery, this surface clarity reveals a more unsettling argument. Inside Out attempts instead to reveal the value of emotional tolerance. Its deepest claim is not that happiness comes from managing feelings well, but that constant contradiction of emotion is necessary to create identity.

I. Continuity

Joy begins the film as the keeper of continuity. She treats Riley’s inner life as something to be curated, and protected from contamination. Sadness, in her view, corrodes life. If sadness touches a memory, the memory changes, so Joy fears this potential narrative fracture. However, this fear is prevalent in modern culture. We believe happiness to be stability; we believe it to be a consistent mood, a smooth trajectory. Self-help language also reinforces this fantasy by encouraging us to “protect our peace” as though peace were a fragile artifact rather than a dynamic process. At the beginning of the movie, Joy embodies this impulse, believing that if the right emotions remain in charge, the self will remain intact.

II. Sadness

But Inside Out dismantles this belief. When Sadness touches Riley’s memories, they don’t crack or fracture; rather, they deepen. Riley’s joyful recollections of childhood play become tinged with grief, but not because the joy was false; that grief comes from the memories belonging to a time that cannot be recovered, something we have all experienced. The memory gains depth and complexity, and with that comes narrative truth. What Joy interprets as damage is really just maturation.

The film suggests that unpleasant emotions like sadness are necessary to complete meaning. Only through sadness can experience remain emotionally legible over time. Without it, memories become artifacts, forever frozen, incapable of accommodating change. Riley’s crisis emerges when her emotional system can no longer pretend that continuity is possible. Moving cities disrupt her internal story. Her old sources of meaning, her friends, routines, and landscapes, shift apart. And the attempt to remain cheerful under these conditions produces emotional turmoil.

III. Growing

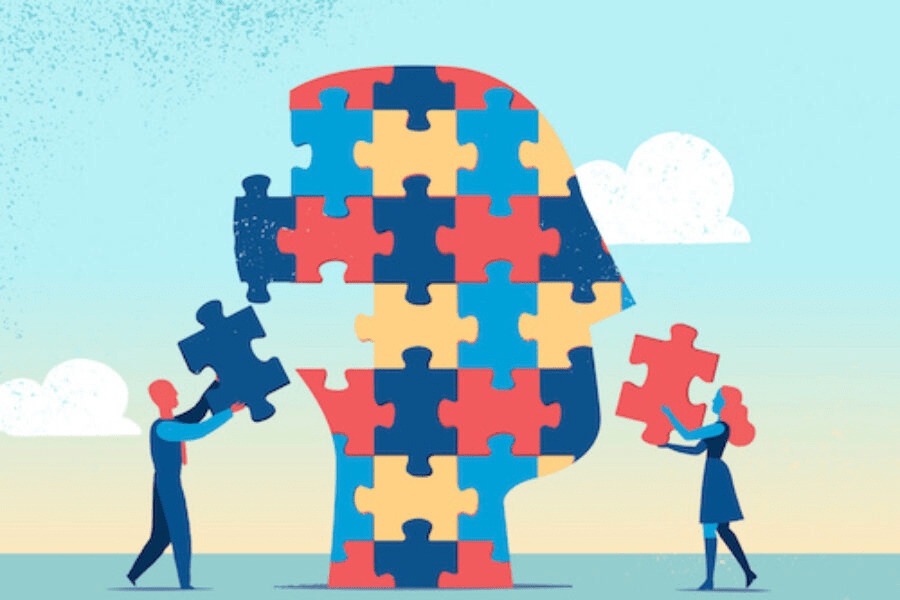

The ultimate resolution to this crisis is not the restoration of Joy’s authority, but a deeper understanding of the emotional hierarchy. When Sadness is allowed to speak, Riley’s pain becomes shareable. The problem isn’t solved, but her parents can help because the problem has been named.

In this sense, Inside Out offers a corrective view to a culture obsessed with emotional optimization. It suggests that unlike popular belief, psychological health is not achieved by minimizing negative states, but by allowing them to rise up to construct meaning. The film implies that identity is a dynamic system that must remain open to revision.

IV. Conclusion

The film ends with memories that shimmer with multiple emotional hues, refusing closure. Riley’s inner life becomes more difficult to map out, but it becomes more real. Every emotion evolves together. If Inside Out has a lesson, it is not that sadness is good, or that joy is naive. The lesson lies in the fact that a self that insists on feeling only one thing at a time will eventually lose the ability to feel anything honestly at all. Emotional maturity, like narrative truth, requires the courage to let experiences change us. Even if it’s hard. Even if it disrupts the story we carry of ourselves. Because to live is to keep becoming, again and again.