Your perfect schedule is already built in to your brain, here’s how to find it.

Ever wonder what a perfect day would look like if your brain actually cooperated? As a student, I’ve spent countless mornings staring at my planner, wondering how to get everything done without going crazy. Between lectures, homework, and the never-ending influx of notifications, it often feels impossible to stay focused or energized. Luckily, neuroscience has some surprisingly practical answers, tools and insights you can actually use to design a day that works with your brain, not against it.

Sleep: The Non-Negotiable Starter

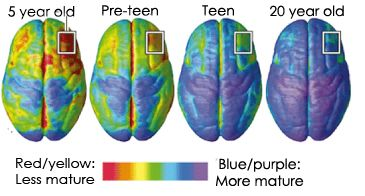

Your neurons are night-shift workers. They do not take coffee breaks. Deep sleep is when your brain consolidates memory, prunes connections, and basically declutters itself. Skipping it is like trying to run your laptop with twenty tabs open and battery at 10%. For students, this means late-night cramming is usually self-defeating. Your brain might get the homework done but it will forget half of it by tomorrow. I know it’s hard, but please aim for 7-9 hours and try to stick to a consistent schedule. Your future self will thank you.

Timing Matters

Your brain does not operate at full power all day. For most people, mornings are best for focus-heavy tasks like writing essays or solving math problems. Afternoons are better for lower-stakes or social tasks because your alertness naturally dips. Evenings, surprisingly, are when creativity peaks, making it the perfect time for brainstorming, art, or revising your philosophy blog. Mapping your most important tasks to your brain’s natural rhythms is like scheduling meetings with your most demanding client, which happens to be yourself.

Work in Bursts

Attention is a finite resource. The brain has ultradian rhythms, cycles of about 90-120 minutes of high alertness followed by a dip. Working for long stretches without a break is like driving a car without refueling. Try focusing for 25-50 minutes, then take a 5-10 minute break. Walk around, stretch, or just stare out the window. Your neurons actually perform better when given a pit stop.

Tiny Wins and Dopamine

Dopamine is the brain’s reward molecule. It helps you pay attention, remember things, and feel good while doing them. Checking your phone releases dopamine, which is why it’s so addictive. You can hack the system by rewarding yourself for small accomplishments. Finish a paragraph or send an important email, then treat yourself to a song or a snack. These micro-rewards keep motivation high without falling into the trap of procrastination disguised as productivity.

Flow Is Your Friend

Contrary to popular belief, your brain cannot multitask. It can only switch attention quickly, leaving a trail of incomplete thoughts. Flow happens when your skill level matches the challenge in front of you. That sweet spot where time disappears is the perfect zone for productivity. Batch similar tasks, eliminate notifications, and dive in without guilt. Flow loves focus, and your brain will thank you with higher quality work and less stress.

Move Your Body

Even a 10-minute walk or a few stretches trigger brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. This protein helps neurons grow and stay flexible. Movement literally helps your brain work better. Try walking to class, stretching between study sessions, or even dancing in your room. It’s scientifically proven to reduce stress while boosting energy.

Reflect and Reset

Reflection is where your brain consolidates memory, processes mistakes, and primes itself for tomorrow. Journaling, meditating, or just mentally replaying the day helps you learn from experience. 5 minutes of reflection at the end of the day can provide actionable insights and make tomorrow feel a little less chaotic.

The Takeaway

A perfect day is not about cramming more hours into your schedule or pretending to be a productivity robot. It is about designing your environment, your tasks, and your mindset around how your brain actually works. Sleep, flow, movement, timing, rewards, and reflection are the ingredients. Layer them thoughtfully and your day becomes less of a struggle and more of a rhythm. With a little planning and a lot of understanding of your own brain, students (like you and me) can actually make each day feel productive, energizing, and maybe even a little magical.

You got this! Now go take the steps, no matter how small, to achieve your goals!

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.