I want my experience to guide me, not undeserved freebies.

I never make wishes. Not because I lack desire, or because I am practical in a boring sense, but because I want the arc of my life to emerge from my choices and mistakes, not from a free handout from the universe. A wish, by its nature, is a shortcut. An attempt to acquire a future without traversing the path that shapes the self along the way. I am more interested in that shaping than in the outcome itself.

Neuroscience

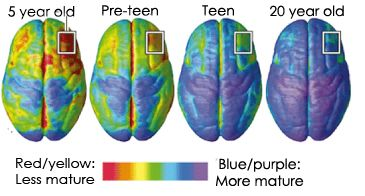

Neuroscience gives a strange kind of validation to this intuition. The brain learns most deeply through effort through what researchers call prediction error, the moment when expectation meets reality and the system adapts. Dopamine spikes which respond to effortful achievement serve to reinforce connections in the prefrontal cortex and striatum, helping us encode both skill and memory. If wishes were real, they would bypass that process. In a sense, it deprives the nervous system of experience, its most potent teacher.

Consider the subtle difference between a student who struggles for months to master a piece of music and one who magically acquires the ability with a single wish. Both may be able to play the notes, but only the first has undergone the kind of plasticity that transforms the mind. The hippocampus consolidates memories, the motor cortex refines its output, and the brain’s error-monitoring circuits, especially in the anterior cingulate cortex, learn to adapt. The journey, not the shortcut, builds agency. The wish, however tempting, is neurologically inert. Sorry, Aladdin. It asks nothing and returns nothing of value beyond the superficial.

Philosophy

Philosophically, my aversion to wishing aligns with existentialist thought. Kierkegaard wrote about authentic existence as reliant on decision, risk, and reflection. To hand over the authorship of your future, even symbolically, to some external wish is to abdicate the very process that makes life meaningful. Wishing collapses experience into instant gratification; it divorces outcome from effort, action from responsibility. And the self, stripped of its formative trials, becomes lighter, but also emptier.

Stories like Aladdin illustrate a subtle truth about wishing and effort. Aladdin becomes wealthy, meets the princess, and transforms his life, but only because the narrative allows him access to opportunity. In real life, outcomes are far less generous. Contemporary philosophy and social thought remind us that effort alone does not guarantee escape from suffering. Structural barriers, resources, and circumstance shape who can act on their potential and who remains constrained, no matter how hard they try. Refusing shortcuts or wishes is therefore a personal ethical choice because it shapes the kind of person you become, but it cannot erase the imbalances of reality. What we gain from experience is valuable, but it is never distributed evenly.

Therefore, this is not to romanticize suffering or struggle. I am not advocating for unnecessary pain or the glorification of difficulty. But I do believe that real growth requires living inside the friction of consequence and choice.

Ethics

There is also a subtle ethical dimension. When we wish for unearned advantages, we are implicitly saying that we value our own gain above the discipline of learning or merit. By refusing to wish, I am also, in a small way, refusing to outsource my development to luck. I am committing to a life where reward is proportional to engagement, where consequence is respected, and where experience remains my guide.

The Reality

Sometimes life is harder, slower, and less immediately satisfying than it would be if wishes were real. I miss opportunities that might have arrived on a whim. I watch others take shortcuts and sometimes envy their efficiency.

And yet, I want my story written in synapses that were built in response to challenge, not circumstantial fortune. I want my character shaped by choices that left a mark both on my mind and on my life. The wish tempts me with speed, but I choose depth. I choose learning. I choose experience.

Because in the end, it is experience, not magic, that teaches us who we are.

Written by Mason Lai, a California high schooler.